The Public Health Approach to Preventing Violent Crime

An important part of public health is considering what people need in order to thrive and what happens when those needs are not met. For example, financial security, a stable home environment and a sense of belonging all contribute to one’s well-being. On a community level, many people are deprived of these basic necessities, according to Wil Crary, associate program manager for The Prevention Institute.

“A lot of things may not be structurally provided because of a lack of resources in the community based on systemic oppression or intergenerational poverty,” Crary said. “So, you might [find] alternative paths to meet some of those needs—that could mean joining a gang. You find financial stability and a sense of belonging and connection through gang involvement because that is the survival tactic presented to you.”

These alternative paths can lead to negative experiences, including a heightened exposure to violence. The increased risk of experiencing or witnessing violence can then lead to poor health outcomes. For this reason, Crary, along with other public health professionals, focuses his work on taking a preventive approach by identifying root causes of community violence.

What Are the Effects of Community Violence on Public Health?

When talking about violence prevention and the effects of violent crime on public health, there are many types of harm that can be considered “violence.” This can include:

- Domestic abuse

- Guns

- Physical injury

- Sexual assault

- Child neglect

It is also imperative to consider structural violence, or harm caused by structural factors that prevent individuals from gaining access to things like healthcare, quality education and secure housing. Trauma caused by these types of violence can manifest at the individual and community levels.

“[Violence prevention] needs to be comprehensive, and it needs to bring together multiple sectors so that we’re not siloed in how we approach these issues and how we create solutions.”

-Wil Crary, Associate Program Manager for The Prevention Institute.

For example, a person who encounters violence may experience mental and physical health issues, such as post-traumatic stress disorder and injury. Individuals can also experience harm from witnessing violence as a bystander or hearing about violent events in their community.

On a community level, experiencing violent events in addition to facing structural violence can result in collective trauma with rippling effects, according to “Adverse Community Experiences and Resilience,” a resource created by the Prevention Institute. Community trauma can cause a breakdown of social networks and positive social norms, elements that are helpful in protecting against violence and other negative health outcomes.

Mental and Physical Health in Victims of Violence

The ways in which violence can affect health extend beyond risk of injury. Individuals with adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are more likely to experience chronic health problems (e.g., cardiovascular disease), mental health conditions (e.g., depression) and substance use problems as adults, according to a guide on ACEs from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Past experiences of violence can also influence the ways people interact with their environment and the people around them. For example, research has shown that individuals who fear violence in their neighborhood engage in less physical activity. When the ability to feel safe while exercising outdoors is taken away, community members can experience poor health outcomes as a result.

In addition, fear of violence can contribute to chronic stress, which is linked to poor health outcomes. Conditions related to chronic stress include:

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic fatigue

- Depression

- Gastrointestinal issues

- Hypertension

- Immune disorders

- Obesity

- Stroke

Community Violence and Childhood Trauma

The ways in which exposure to violence specifically affects children and adolescents is another area of concern for public health. Studies have shown that children who are frequently exposed to violence are at a higher risk for developing behavioral problems, depression, anxiety and increased signs of aggression. When taking a preventive approach to addressing the effects of community violence, having conversations with children can help them process trauma and minimize potential negative outcomes.

How to Talk About Violence and Trauma With Children

Consider their age. It’s important to tell the truth when a child asks a question, but their maturity and level of understanding should be taken into consideration when discussing a recent or ongoing traumatic event.

Be realistic. Children will look to supportive adults when they feel unsafe, and creating a safe environment requires trust. Instead of promising a child that nothing bad will happen—an uncertainty everyone faces—focus on comforting them through things that can be controlled (e.g., “I will do what I can to keep us safe”).

Actively listen to them. This sympathetic and respectful action shows a child that they are heard and their feelings are valid. It also lets them set the tone for what they are comfortable talking about with a parent or trusted adult.

Recognize signs of distress. If a child is displaying behavioral issues, their behavior could be a sign they are struggling to cope with their trauma. In these cases, shaming or isolation-based punishments can do more harm. A trauma-informed response to their behavior can help them feel safe.

Seek help when necessary. If there is concern about how a child is coping with a recent event or ongoing issues, consider contacting their pediatrician or a mental health provider for additional support.

Sources:

Violent Crime in Marginalized Communities

Communities that experience higher rates of violence often have populations of marginalized people. However, this is not to say marginalized people are more likely to engage in violent crime; rather, Crary explained that there are often external factors at play.

“The original act of violence is depriving young people of stable housing, that there are young people in the community who don’t have access to the food that sustains them, and that their schools are underfunded,” Crary said.

According to a CDC resource on community violence, social determinants of health—such as racism; economic instability; and limited access to housing, education and healthcare—contribute to the prevalence of community violence and other health disparities.

Because of these interlinking root causes, marginalized groups—including BIPOC communities and low-income communities—often bear the brunt of violent crime.

Data shows that Black, Indigenous and Hispanic or Latino people have higher homicide rates than other racial and ethnic demographics. Research has also found that individuals living in low-income households have higher victimization rates for all types of personal crime.

In one particular study, researchers examined violence-related health disparities experienced by Black people and found that Black Americans are at higher risk for dying by homicide than their white counterparts.

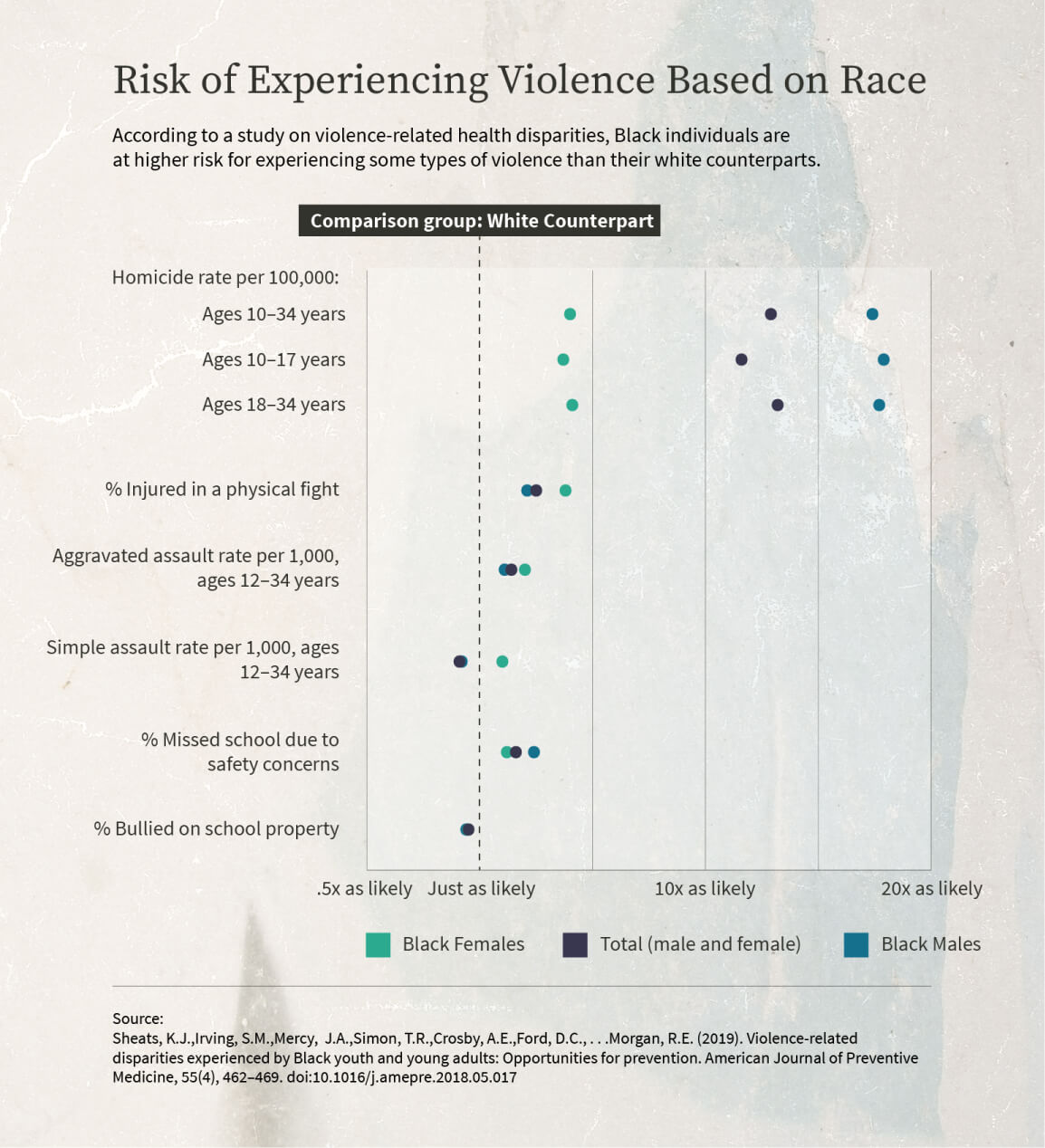

Risk of Experiencing Violence Based on Race

A study on health disparities related to violence indicates that Black men ages 10–34 have 17.4 times the risk of homicide as white men the same age. Go to a tabular version at the bottom of this page.

Public Health and Violence Prevention

With regards to interventions for community violence, Crary explained there are three levels of action:

Primary:

preventive measures taken to avoid an event

Secondary:

support provided during an event

Tertiary:

services provided after an event to address lasting effects

While secondary and tertiary interventions are necessary, the public health approach to violence brings more focus to primary interventions—solutions that are meant to stop a problem before it starts.

“[Violence prevention] needs to be comprehensive, and it needs to bring together multiple sectors so that we’re not siloed in how we approach these issues and how we create solutions,” Crary said.

What Does Violence Prevention Look Like?

Interventions for violence and community trauma may not immediately appear to be related, as there are several factors that contribute to the prevalence of violence. Addressing three primary areas related to community resilience (PDF, 2.4 MB) can contribute to reducing violence:

Social-cultural environment

refers to community relationships, social norms and the ways people interact with each other.

The Kalihi Valley Instructional Bike Exchange shows how organizations can improve the social-cultural environment. While this community program focuses on encouraging physical activity by increasing access to bicycles, it also creates a sense of belonging for those who participate in the exchange and offers individuals the ability to learn new skills such as bike repair.

Physical and built environment

includes the structures within a community that affect how people live and access resources.

Initiatives to improve roads, buildings, parks and transportation can encourage positive social interaction and relationships in communities. The built environment of a community can also encourage or discourage healthy behaviors and activities.

Economic opportunity

is the community members’ ability to participate in an economy, gain employment and access necessary resources.

An example of improving economic opportunity is the facilitation of reentry for individuals who were formerly incarcerated. Reentry services, such as the correctional reentry program offered by Volunteers of America, help individuals navigate barriers to secure housing, employment and other services. In doing so, reentry programs aim to reduce recidivism caused by preventable parole violations (e.g., failure to maintain lawful employment).

Resources on Violence Prevention

APHA | Violence Is a Public Health Issue

This article from the American Public Health Association explains the impact of violent crime on public health and provides insight on how communities can take a public health approach to violence prevention.

CDC | Injury Prevention & Control

The CDC provides a variety of resources on injury prevention, violence-related issues and protection and support for children and adolescents.

Healthy People 2030 | Crime and Violence

This report by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services explains how the built environment contributes to rates of violent crime and explores the health implications of this issue.

This nonprofit organization aims to provide support to victims of violence and take proactive steps toward violence prevention.

Institute on Domestic Violence in the African American Community IDVAAC

IDVAAC focuses on the unique circumstances of African Americans in its efforts to address the issue of domestic violence.

National Center for Victims of Crime

Aiming to “serve individuals, families and communities harmed by crime,” the National Center for Victims of Crime offers a variety of resources and services to victims of all types of crime.

National Coalition Against Domestic Violence

Focusing on the conditions that lead to domestic violence, the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence advocates for violence prevention and provides resources for individuals experiencing domestic violence.

National Domestic Violence Hotline | Domestic Violence Support

The National Domestic Violence Hotline provides a safe, secure service for those experiencing domestic violence to call, text or live chat as well as other helpful resources.

Prevention Institute | Adverse Community Experiences and Resilience (PDF, 2.4 MB)

This extensive guide explores the concept of community trauma and provides a framework for improving resilience among community members affected by violence and other types of harm.

With a focus on violence prevention, this report covers the interlinking causes of different types of violence.

WHO’s resource page on violence prevention links to examples of the organization’s work in this area, along with related news and other information.

The following section contains tabular data from the graphics in this post.

Violence Exposure for Non-Hispanic Blacks and Non-Hispanic Whites by Sex

| Variable | Black to white RR (Male) | Black to white RR (Female) | Black to white RR Total (male and female) |

|---|---|---|---|

Homicide rate per 100,000 (Ages 10–34 years) | 17.4* | 4.0* | 12.9* |

Homicide rate per 100,000 (Ages 10–17 years) | 17.9* | 3.7* | 11.6* |

Homicide rate per 100,000 (Ages 18–34 years) | 17.7* | 4.1* | 13.2* |

% Injured in a physical fight | 2.1* | 3.8* | 2.5* |

Aggravated assault rate per 1,000, ages 12–34 years | 1.1 | 2.0* | 1.4* |

Simple assault rate per 1,000, ages 12–34 years | 0.8* | 1 | 0.9 |

% Missed school due to safety concerns | 2.4* | 1.2 | 1.6* |

% Bullied on school property | 0.6* | 0.52* | 0.5* |

*statistically significant value

RR = Risk Ratio or Relative Risk