Understanding Homelessness as a Public Health Issue

Homelessness is often viewed as an economic and social issue, but homelessness and the broader problem of housing instability are also matters of public health.

“The significance of the relationship between an individual’s housing and health status cannot be overstated,” Erin Kelly, MPH, wrote in an op-ed for Newsweek on homelessness and health. “Housing instability harms health both directly—by moving people away from their doctors and into unsafe housing—and indirectly—by causing stress and eliminating resources that could otherwise keep people healthy.”

Individuals experiencing homelessness are more likely to have chronic physical and mental health conditions. In fact, being unhoused “creates new health problems and exacerbates existing ones,” according to a publication from the National Health Care for the Homeless Council (PDF, 340 KB).

There are many models that can help address the challenges faced by people experiencing homelessness to improve their quality of life and minimize their health risks. Public health professionals and community members alike can advocate for these solutions at the local, state and national level.

Why Is Homelessness a Problem?

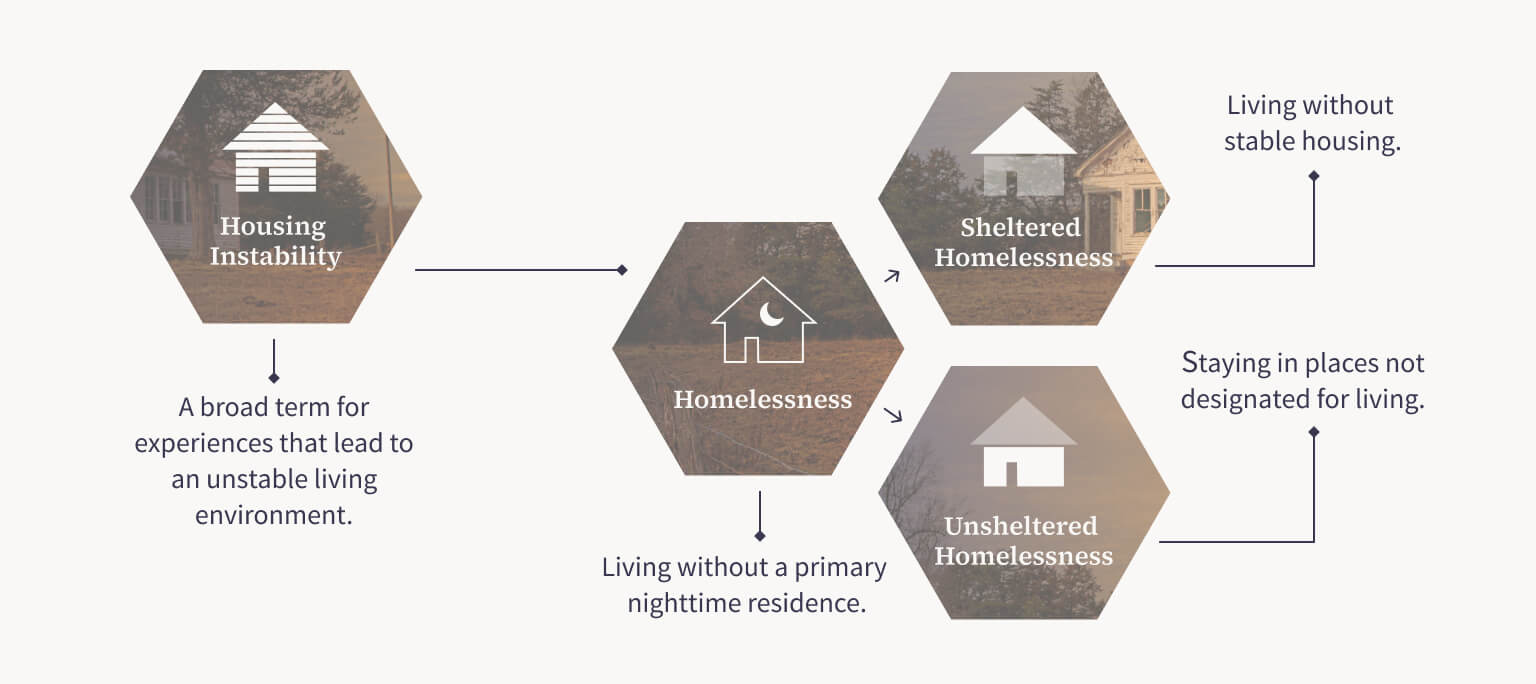

Housing instability occurs on a spectrum and can present in many different ways. The terms below help describe experiences that fall under the umbrella of housing instability and homelessness, and they offer insight into how housing issues affect individuals differently.

What Is “Homelessness”?

Terms to Describe Housing Instability and Homelessness

Transitional homelessness describes a period of homelessness that lasts for weeks or months, but no longer than one year.

Episodic homelessness

means entering and leaving homelessness repeatedly, often due to unstable housing situations.

Chronic homelessness

refers to experiencing homelessness for a period of at least one year.

Sources:

- Behavioral Health Services For People Who Are Homeless (PDF, 825 KB). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2021. Accessed April 19, 2021.

- 2021 AHAR: Part 1 – PIT Estimates of Homelessness in the U.S. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, February, 2022. Accessed April 19, 2022.

- Healthy People 2030. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2020. Accessed April 19, 2021.

How Many People Experience Homelessness in the United States?

The total number of people experiencing homelessness can be difficult to estimate, as some individuals live without shelter and move frequently. However, annual reports from government agencies and other organizations provide insight on the populations most affected by homelessness. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) highlighted the following numbers:

326,000

The number of people experiencing sheltered homelessness on a single night in 2021 in the United States.

20%

The increase in the number of sheltered individuals experiencing chronic homelessness between 2020 and 2021.

<1%

The decrease in the number of unsheltered individuals experiencing homelessness on a single night between 2020 and 2021.*

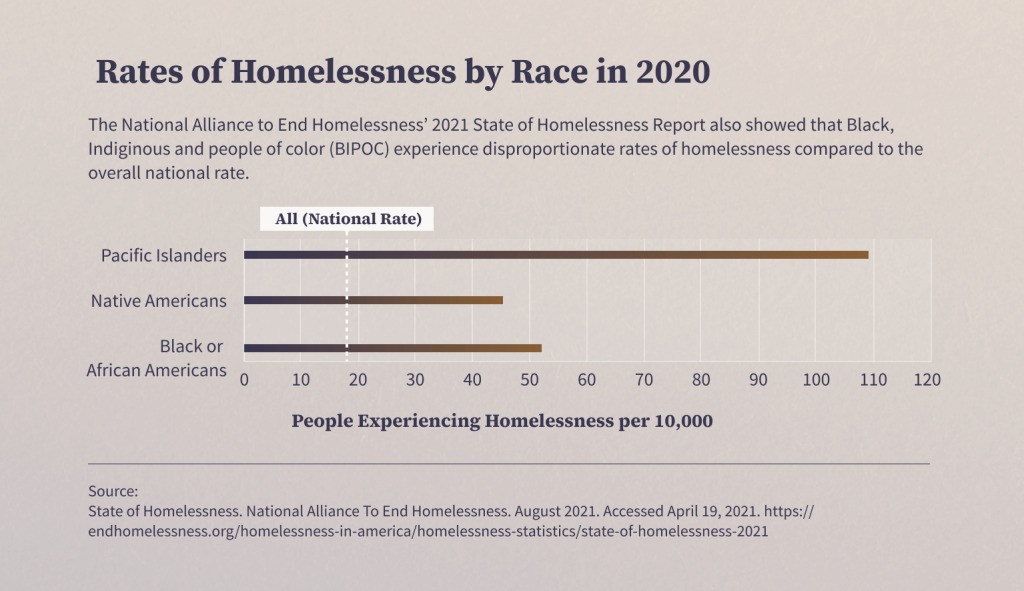

According to data from 2020, Pacific Islanders, Native Americans, and black people all experienced a rate of homelessness that exceeded the overall national rate.

Go to a tabular version of the “Rates of Homelessness by Race” at the bottom of the page.

What Are the Effects of Homelessness on Health?

Social determinants of health are “conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning and quality-of-life outcomes and risks,” according to the U.S. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Economic stability is one social determinant of health that encompasses housing instability and homelessness.

The connection between homelessness and health outcomes goes both ways. People with chronic health conditions are more likely to experience homelessness or housing instability; likewise, experiencing homelessness or housing instability can have additional negative effects on one’s physical and mental health. This relationship between homelessness and health outcomes creates a cycle that can be difficult to overcome.

People experiencing homelessness are:

- Three to four times more likely to die prematurely.

- Two times as likely to have a heart attack or stroke.

- Three times more likely to die of heart disease if they are between 25 and 44 years old.

These health outcomes stem from a variety of factors. According to a policy statement from the American Public Health Association (APHA), people experiencing homelessness have high rates of chronic mental and physical health conditions. Their lack of housing creates barriers to accessing healthcare and following healthcare directives, such as adhering to prescription medication regimens.

Substance use is also a challenge for the homeless population. Research has shown that over one third of individuals experiencing homelessness have problems with alcohol or drug use.

How Can Homelessness Be Addressed?

When people can access stable, safe housing, they can experience better health and quality of life. In turn, they can more easily remain housed. While there is not one perfect solution to the issue of homelessness, there are a number of models that have shown positive results:

Housing First

Instead of requiring individuals to achieve “housing readiness” to qualify for a program, the Housing First approach provides permanent housing as a foundation so individuals can then address other issues, such as getting sober, receiving care for mental and physical health issues, and seeking employment.

Permanent supportive housing

This model combines safe housing and supportive services for individuals with mental health issues or other conditions that require services to maintain housing stability.

Decriminalization of homelessness

Laws that criminalize behaviors associated with homelessness, such as camping bans, fail to address the root causes of homelessness; instead, punitive measures cycle individuals through the criminal justice system, where they may be exposed to additional health risks. Alternative approaches that do not involve criminal punishment can help minimize harm to people experiencing homelessness.

Homelessness prevention

Taking proactive steps to support those who are at risk for experiencing homelessness can help individuals find stable housing. For example, programs for young adults who age out of the foster care system can help connect them with housing resources. Community re-entry programs for individuals who experienced incarceration can also support people in securing employment and housing.

Sources:

- Permanent Supportive Housing. Center for Evidence-Based Solutions to Homelessness, 2017. Accessed April 19, 2022.

- What Is Housing First? National Alliance to End Homelessness, April 20, 2016. Accessed April 19, 2022.

- Flacks, Chuck. Five Alternatives to Sanctioned Encampments or Criminalizing Homelessness. International City/County Management Association, March 17, 2022. Accessed April 19, 2022.

- Housing and Homelessness as a Public Health Issue. American Public Health Association, November 7, 2017. Accessed April 19, 2022.

Resources About Homelessness and Health

Resources For Advocates

- Advocacy | Health Care for the Homeless

- Health & Homelessness | American Psychological Association (PDF, 127 KB)

- Health | National Alliance to End Homelessness

- Homelessness as a Public Health Law Issue | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Homelessness & Health: What’s the Connection? | National Health Care for the Homeless Council (PDF, 340 KB)

- How Can I Advocate on Behalf of Homeless Families? | National Coalition for the Homeless

Resources For Individuals Experiencing Homelessness

Resources For Homelessness Prevention

Resources For Supporting Children Experiencing Homelessness

The following section contains tabular data from the graphics in this post.

Rates of Homelessness by Race in 2020

| Group | Rate of homelessness |

|---|---|

All (National Rate) | 18 out of every 10,000 people |

Pacific Islanders | 109 out of every 10,000 people |

Native Americans | 45 out of every 10,000 people |

Black or African Americans | 52 out of every 10,000 people |